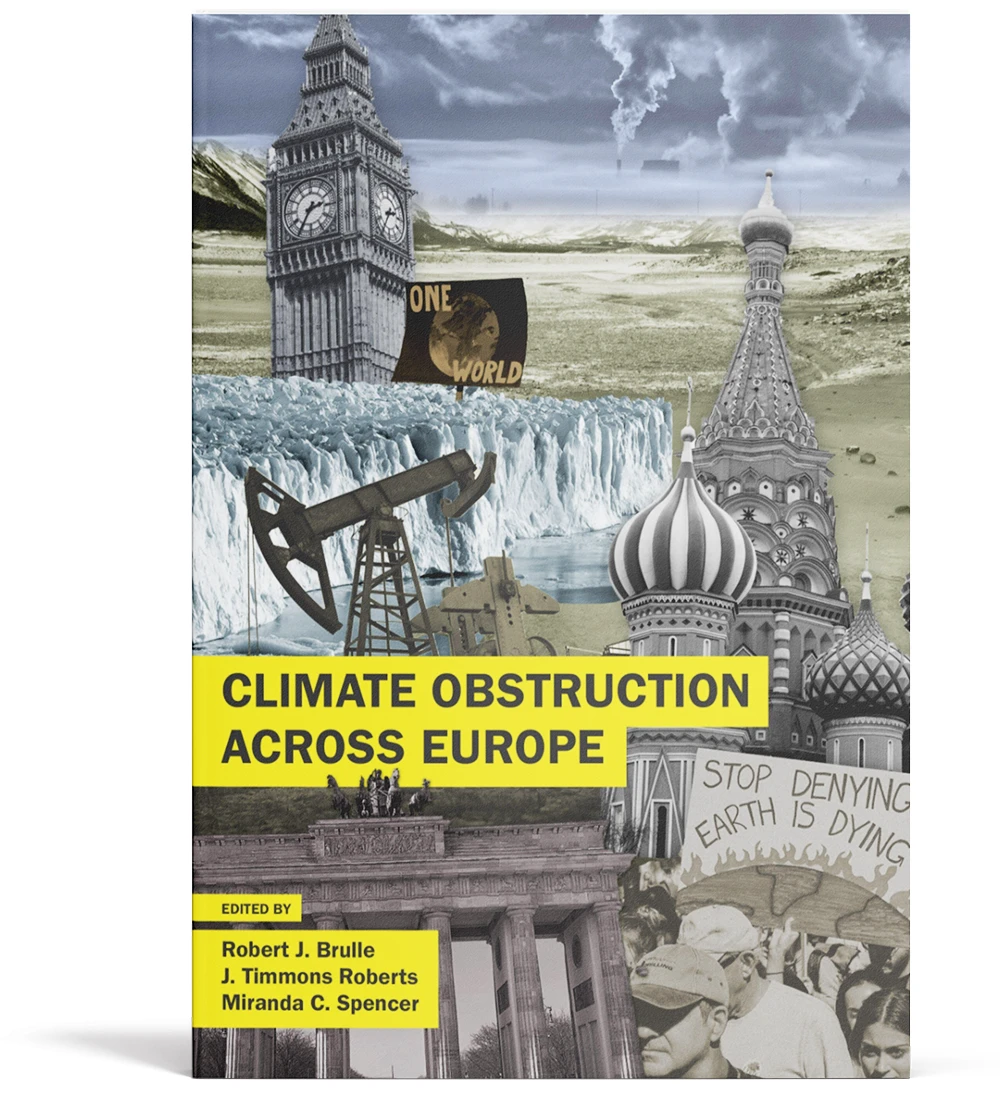

Climate Obstruction Across Europe, coordinated by the Climate Social Science Network (CSSN) and published via Oxford University Press, reveals extensive networks impeding climate action within the region and surrounding states.

Climate Obstruction Across Europe, coordinated by the Climate Social Science Network (CSSN) and published via Oxford University Press, reveals extensive networks impeding climate action within the region and surrounding states.

In Italy and Germany, far-right networks spread misinformation by questioning climate science’s validity, while in Spain and the UK, blame-shifting and deflecting responsibility for climate action are common. European-based fossil fuel industries, like Shell, engage in greenwashing, by framing gas as a ‘bridging technology crucial for the energy transition’, delaying genuine progress.

Climate obstruction is defined in this book as intentional actions and efforts to slow or block policies on climate change that are commensurate with the current scientific consensus of what is necessary to avoid dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.

This obstruction isn’t just anti-climate-action; it’s anti-democratic as it obstructs transparent decision-making, distorts public discourse, and undermines the public’s right to accurate information. Shedding light on these actors and tactics is crucial for informed climate policy decisions, particularly in light of the upcoming EU elections.

Despite widespread public backing for the UK’s legally binding goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050 and the economic benefits it could bring, climate obstructionists deploy a variety of tactics and strategies to maintain dependence on volatile and dangerous fossil fuels.

Organised sceptic groups and think tanks (e.g. Global Warming Policy Foundation, Net Zero Watch), media (particularly right-leaning papers such as The Daily Telegraph and The Daily Mail), business and trade associations (e.g. CBI), government actors and institutions.

In Scotland, key industry and political figures use deceptive tactics to promote oil and gas, and delay critical climate action, framing these as ‘essential for energy security’ and ‘necessary bridging’ fuels.

Fossil fuel companies (e.g., BP, Shell, INEOS), trade unions like UKOOG, business and trade associations, and political figures linked to the oil and gas sectors.

In Ireland, high carbon sectors like agriculture leverage cultural and lobbying power to divert concern from livestock emissions, delaying climate action and protecting their interests.

Irish agri-food sector, lobbyists (e.g., Irish Farmers Association and Irish Business and Employers Confederation), and historically, high-profile climate contrarians.

Despite Sweden’s high public consensus for more significant climate measures and amidst intensifying climate threats, climate obstructionists, increasingly intertwined with the far-right, are thwarting progress through undemocratic tactics.

The Sweden Democrats, a far-right political party, corporate interests (e.g. Confederation of Swedish Enterprise (SAF)), think tanks (e.g. Timbro), and industrial sectors.

Germany’s ambition for a cleaner future is under siege by a climate obstructionist network, skillfully delaying decarbonisation efforts. Unrestrained, it threatens to compromise a safer and more prosperous future and diminish Germany’s position as a global Greentech leader.

Fossil fuel producers (e.g. RWE, Vattenfall), industrial corporations (e.g. Aurubis AG), business associations (e.g. Association of the German Automotive Industry), and think tanks (e.g. EIKE).

In the Netherlands, climate obstructionists linked to fossil fuels use doubt and delay tactics while emphasising their corporate responsibility and questioning climate science.

Climate denialists with former connections to the fossil fuel industry (e.g. Frits Böttcher and Guus Berkhout), Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy (a government body that has consistently opposed stricter climate regulations), employer’s organisations (VNO-NCW), lobby groups (ABDUP, PHAUSD), Shell.

Poland’s significant potential to benefit from becoming a key player in the global green economy is thwarted by a network of powerful, fossil-fuelled climate obstructionists.

Governmental institutions (Ministry of Climate and the Environment, the Ministry of State Assets), state-owned energy companies (e.g. Orlen and PGE), political figures, think tanks and media.

In Russia, a network of climate obstructionists are using tactics to downplay climate urgency. These include for example leveraging media control and geopolitical narratives.

Government and political leaders, state-controlled media, industry (including Gazprom, Rosneft), and a minority of scientists (with ideological reasons for their denialism).

In the Czech Republic, political figures, parties, and think tanks fuel climate disinformation, employing media and other tactics to shape public perception and maintain the status quo.

Mainstream politicians, political parties (e.g. Civic Democratic Party (ODS), ANO 2011 Party), think tanks (e.g. Václav Klaus Institute), and media.

Dominated by fossil fuel companies, with Eni at the forefront, alongside think tanks, media outlets, politicians, political parties, financial institutions, and banks, a network employs a range of tactics to thwart critical climate progress in Italy.

Fossil fuel companies and industry groups (e.g. Eni, Snam, Confindustria), politicians and political parties (particularly right-wing, e.g. Brothers of Italy), think tanks (e.g. Istituto Bruno Leoni), individual climate deniers, media, financial institutions (Banks like Unicredit and Intesa Sanpaolo).

The fossil fuel sector and its network of climate obstructionists have strategically blocked Spain’s progress towards decarbonisation, particularly in expanding renewable energy use. This coalition risks opportunities for green economic growth in Spain, driving escalating energy bills, and confronting an increasingly uncertain future.

Politicians (e.g. Conservative PP, Vox), the energy sector (e.g. AELEC, the Nuclear Forum, Sedigás, Carbunión), big agriculture (e.g. Interporc and ANICE), think tanks (e.g. FAES and the Juan de Mariana Institute), and the media.

Fuelled by fossil interests, thousands of climate obstructionist firms and business lobbies deploy numerous tactics to stifle progress, blocking green investment opportunities and endangering the EU’s stature as a global climate leader.

Fossil fuel companies and energy utilities, automotive manufacturers, big agriculture companies, think tanks and industry associations (e.g. BusinessEurope, Eurofer).